When you hear “descendants of Confederates” who do you picture?

Maybe you imagine a Confederate flag-waving White country boy? Or do you picture an older White man with a crisp business shirt who attends monthly Sons of Confederate Veterans meetings? Perhaps you imagine a fancy white-glove wearing elderly White woman who defends statues of Confederates?

But why?

There are millions of descendants of Confederates alive today. Why do we picture folks like these — folks who revere the Confederacy?

To imagine that most descendants of Confederates venerate the Confederacy is a cognitive bias that is hurting us. Venerators may be organized and vocal, but their views do not represent most descendants. Daniel Kahneman, in his book Thinking Fast and Slow, describes a cognitive bias called “what you see is all there is.” In this case, if we don’t see descendants of the Confederacy who are against its reverence, then we assume they must not exist. The danger here has been that venerators are allowed to speak on behalf of all descendants of Confederates.

I’ve long suspected that most descendants of Confederates want to see the relics of their ancestors’ “rebel nation” disappear. I think most descendants understand that memorializing the Confederacy is keeping open the wounds of this country, not just the civil division between north and south, but it maintains a racist ideology that regards the enslavement of Africans as tolerable (at best).

I think most descendants understand this, but “seeing” them has been a challenge. Here’s why.

First, you already know that millions of Black Americans are descendants of Confederates, right? You knew that. Most are likely descendants through brutal rape and “slave breeding”, but they are descendants just the same. That’s an obvious truth that gets overlooked, likely because it’s painful to remember.

We need to picture Black Americans as descendants of the Confederacy, because it is true and their voices matter.

Second, and this is the crux of my point here, I suspect that most White descendants of Confederates have felt shamed to silence, so we simply don’t hear from them. A recent Politico article offers some evidence that most descendants of Confederates, even of Confederate “heroes,” say little publicly but believe their ancestors’ names and images should be removed from public spaces.

As White people with this heritage begin to accept the truth – that the Confederate cause was not just, that slavery was abhorrent, and that the resulting systemic racism has provided an unearned advantage to them – well that can be a genuine source of shame. Many would rather forget their Confederate ancestry and wish everyone in their family would as well. They may fear anyone knowing of their Confederate ancestry, lest they be held personally accountable for the evils of their ancestors. In fact, they may not even tell their children of this ancestry. Indeed, I discovered my connection as an adult and my father claimed to not know.

Or worse, they may fear being mistaken as the kind of descendant who venerates the Confederacy.

Such a fear is not far-fetched.

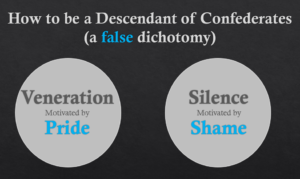

Folks seem to assume a false dichotomy that there are only two ways to be a descendant of confederates: either you are a venerator or you should feel shamed to silence. If a descendant speaks of their ancestry, they are suspected of either being a venerator or someone engaging in performative shame.

I’ve witnessed this assumption a few times myself.

Recently, I’ve been speaking out about my Confederate heritage to my local paper and speaking at racial justice groups. After one article ran, in which I explained I was against Confederate named schools and yes, I am a descendant, an upset White woman called me. “Don’t try to use your ancestry to validate your opinion; that will backfire. Surely most descendants will disagree with you and you don’t want to validate their position.” She whispered to me, “I’m a descendant, too, and you don’t hear me going around and telling people about it. My family is ashamed! You should be, too.” At the conclusion of a talk I gave a Black woman raised her hand and said through measured breath, “I don’t understand you. What do you think you will get out of this?” Perhaps she was suspicious that my motivation might be to soothe my shame. She might have wondered if I was seeking “cookies” and congratulations to appease my guilt. Or was I seeking “self-flagellation,” a sadistic desire to inspire public blow-back for my heritage?

Both of these women assumed the false dichotomy that if I am not proud of the Confederacy that I should feel shame and be silent – so which is it? Pick one.

Burdened by shame White people are pretty useless as advocates for racial change. Our efforts can end up being “self-centering” as we seek to ease our shame. Or we can project our shame onto others and feel righteous (though ineffective) as we blast racism skeptics in an attempt to shame them, a diversion technique so that attention is not paid to our own shame.

Shame is a not a starting place for change-making. If White descendants of Confederates want to be allies, we need a new starting place.

I’m proposing a “third way” to be a descendant of Confederates that rejects both pride and shame. The motivation is not veneration nor guilt. In the third way, descendants are motivated by a special feeling of responsibility which results in actions aimed at changing the way things are and a consequential deep drive to effect lasting systemic change.

[Note: If you wonder how one can hold responsibility but not shame, I suggest reading a previous blog I wrote on the two paradoxical conditions for healing: ownership and self-compassion.]

Envision this with me: What if descendants were successful in changing the (false) narrative of what it means to be a descendant of Confederates? What if, when people picture folks with Confederate heritage, they imagine people — Black, White, and multiracial — who hold a special commitment to destroying White supremacy?